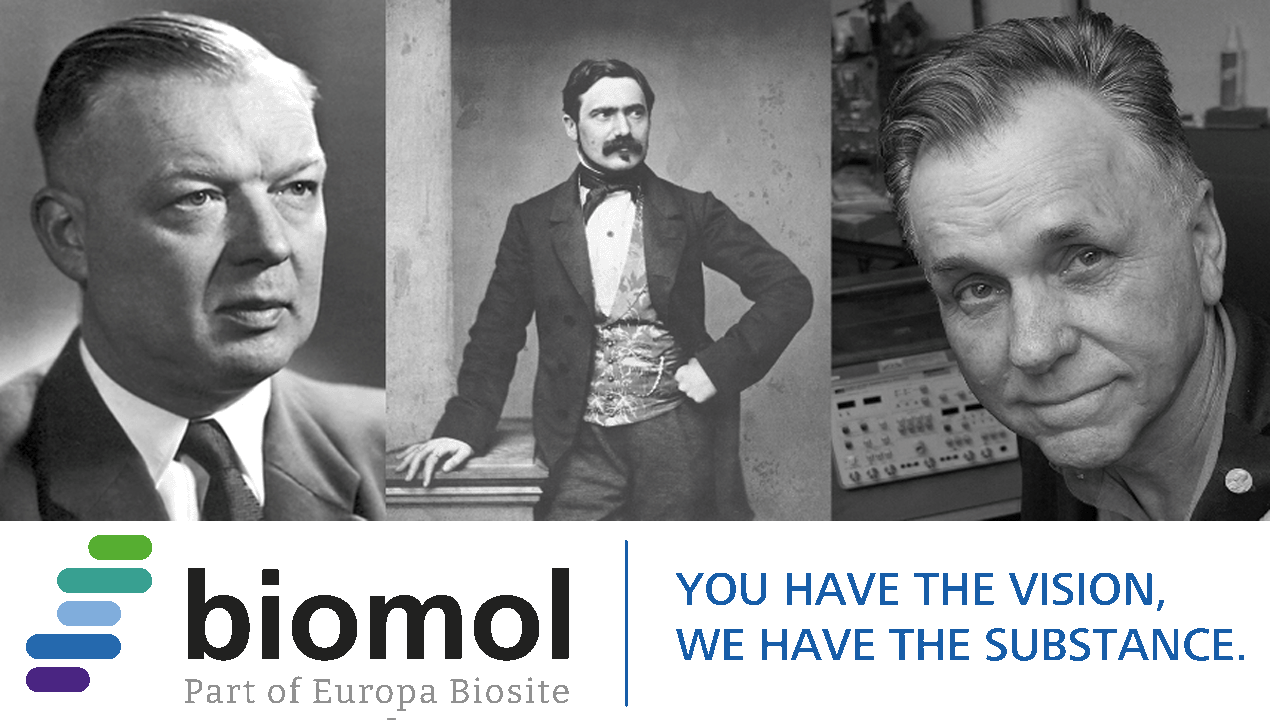

“With such tricks, one earns a habilitation in a circus, not at a respectable German clinic.” [1] With these indignant words, Ferdinand Sauerbruch, then head of the Charité hospital in Berlin, dismissed the young physician Werner Forßmann in November 1929. The reason was a publication in which Forßmann described a medical feat that remains spectacular even by today’s standards: a self-experiment in which, at the age of 25, he inserted a catheter into his own arm vein and advanced it all the way to his right atrium — becoming the first person ever to do so. Already during his medical studies, Forßmann had worked on cardiac diagnostics and experimented with catheterization on cadavers [2]. When his superior strictly forbade any attempts on patients, the young doctor made a drastic decision: secretly, during his lunch break, he inserted a catheter 30 centimeters into a vein in his arm. Then, with the catheter still in place, he went down to the radiology department in the basement, advanced the tube another 30 centimeters, and had an X-ray taken. The result: the tip of the catheter was clearly visible in the right atrium of his heart [1].

Shortly thereafter, the Klinische Wochenschrift published Forßmann’s article “On the Catheterization of the Right Heart” [3]. Yet, as Sauerbruch’s reaction suggests, the paper initially drew little attention within the medical community. Forßmann soon faded into obscurity. Disappointed, he turned to urology and eventually worked as a general practitioner — until, nearly three decades later, recognition finally caught up with him: in 1956, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine “for the discovery of cardiac catheterization and its application to the study of cardiovascular disease” [4]. Forßmann’s self-experiment is not an isolated case in the history of medicine: Again and again, courageous scientists have looked into their own bodies to test their hypotheses. But not all were rewarded for their pioneering spirit — and some paid for their scientific curiosity with their lives.

These topics await you:

1) Brave Exploration of Epidemics

2) Heroes or Madmen? Between Curiosity and the Pursuit of Fame

3) Are Self-Experiments Making a Comeback? Courage in Modern Science

Brave Exploration of Epidemics

Self-experimentation can be found in nearly every area of medicine — but nowhere is the risk of self-harm as high as in the study of infectious diseases. A striking example is the case of Andrew White: In the early 19th century, when British troops were struck by plague and malaria, the physician suspected a connection between the two diseases — and dreamed of developing a protective vaccine against the plague. In 1802, in an Egyptian hospital, White deliberately infected himself with malaria and then smeared pus from the lymph node of a plague patient onto his thigh and into an open wound on his arm. He hoped that his immune system’s response to the malaria infection would simultaneously provide immunity to the plague. But the protective effect he hoped for never came: White developed a high fever, and the lymph nodes in his armpits and groin became swollen — a few days later, he died. This was the first documented self-experiment in plague research, but many others followed: physicians injected themselves with the blood of infected patients, pressed blood-soaked cloths onto fresh puncture wounds, or slept in the clothing of the deceased. It wasn’t until 1894 that the Swiss physician Alexandre Yersin achieved the decisive breakthrough: he identified the plague pathogen Yersinia pestis by microscopically detecting it in the lymph node tissue of victims [5].

Despite the high risks, self-experimentation has played a crucial role in the study of infectious diseases — and continues to do so today. A modern example is the Australian physician Barry Marshall: In 1984, to prove that the bacterium Helicobacter pylori causes stomach ulcers, he drank a foul-smelling suspension made from the stomach contents of an infected patient — a liquid teeming with Helicobacter bacteria. Shortly thereafter, Marshall developed severe gastritis, which he successfully treated with antibiotics [5]. His drastic self-experiment provided the decisive evidence for a paradigm shift in gastric research. Today, testing for Helicobacter pylori is standard in the diagnostic workup of unexplained stomach pain — thanks in no small part to the boldness of its discoverer. In 2005, Marshall was awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine for this discovery [6].

Heroes or Madmen? Between Curiosity and the Pursuit of Fame

The list of researchers who used their own bodies as testing grounds is long: some made groundbreaking discoveries, others paid for their courage with their lives. But what drove them to take such dangerous risks? It wasn’t always a selfless concern for the well-being of others. Often, the motivation lay in a desire for fame, personal vanity, or an unwavering belief in one’s own theory. A particularly stubborn example is the Munich hygiene professor Max von Pettenkofer: in order to prove his rival Robert Koch wrong — namely, that cholera was not caused solely by bacteria — he publicly drank a glass containing a suspension of cholera pathogens. He survived with only a mild intestinal upset, likely because he had developed immunity from a previous infection. Even though Pettenkofer took this as confirmation of his view, history proved him wrong: Koch was right [7].

Like Pettenkofer, many researchers risked their lives with the intention of triumphantly confirming their own theories and securing a lasting place in the annals of science. But alongside the pursuit of fame, genuine scientific curiosity often played a role in driving them to challenge prevailing doctrines [8]. Many of them — including Werner Forßmann — held convictions that clashed with the spirit of their time or were deemed unacceptable. Their self-experiments were not only acts of bravery, but also acts of defiance against dogmatic thinking — and thus paved the way for progress.

Are Self-Experiments Making a Comeback? Courage in Modern Science

Self-experimentation is now a largely outdated method. Today, research questions are first examined through lengthy preliminary studies before regulated clinical trials involving humans are approved — with ethics committees and international guidelines setting clear boundaries. And yet, the self-experiment hasn’t disappeared entirely. Isolated cases still arise in which scientists test new therapies on themselves — driven by conviction, desperation, or pure curiosity. A recent example is molecular biologist Beata Halassy from the University of Zagreb: she researches oncolytic viruses — viruses that specifically target and destroy tumor cells — and decided to treat her own breast cancer using viruses

(You can read more about Beata Halassy and oncolytic viruses in this blog post!)

During the COVID-19 pandemic, self-experimentation experienced a brief resurgence: numerous researchers injected themselves with experimental vaccines they had developed in their own laboratories [10]. This practice sparked controversial debates — especially around ethical and regulatory concerns. Critics warned that such self-experiments could undermine public trust in established vaccine approval processes. In response, scientists from the U.S. and Denmark called on the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to issue clear guidelines and reinforce its regulatory authority in such cases. Without consistent standards, they argued, not only scientific integrity could be at risk — public confidence in the safety and effectiveness of vaccines might also suffer long-term damage [11].

There are numerous examples of self-experimentation throughout medical history. Some ended tragically, while others made significant contributions to science. Today, experimenting on one’s own body is generally the exception rather than the rule, due to ethical and legal considerations. Nevertheless, there are still researchers willing to take personal risks — highlighting how difficult it remains to balance scientific progress with ethical boundaries.

Sources

[1] https://www.aerztezeitung.de/Panorama/Der-Herzkatheter-Selbstversuch-Dichtung-und-Wahrheit-317637.html, 07.06.2025

[2] https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Werner_For%C3%9Fmann, 07.06.2025

[3] Werner Forßmann: Die Sondierung des Rechten Herzens. Klinische Wochenschrift 8 (45), 1929, S. 2085–2087.

[4] https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/1956/forssmann/facts/, 07.06.2025

[5] https://www.aerzteblatt.de/archiv/selbstversuche-forschung-unter-lebensgefahr-f2537b70-673c-49cb-bcbc-1ed03a0faedd, 07.06.2025

[6] https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/2005/marshall/facts/, 07.06.2025

[7] https://www.spiegel.de/geschichte/verrueckte-selbstversuche-a-946798.html, 07.06.2025

[8] https://www.profil.at/wissenschaft/mut-in-der-forschung-die-tollkuehnen-selbstversuche-der-wissenschaft/402584621, 07.06.2025

[9] https://www.zeit.de/gesundheit/2024-11/beata-halassy-selbstversuch-brustkrebs-medizin, 07.06.2025

[10] https://sciencenotes.de/alles-wird-gut/selbstversuch-gegen-corona-2/, 07.06.2025

[11] Christi J. Guerrini et al. Self-experimentation, ethics, and regulation of vaccines. Science 369, 1570-1572 (2020).

Preview Image: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Werner_Forssmann_nobel.jpg?uselang=de, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Max_von_Pettenkofer2.jpg, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dr_Barry_Marshall_-_Nobel_Laureate.jpg?uselang=de, 07.06.2025